The Metaverse: The Metaverse Standards Forum and the Benefits of Standards Development Organizations – Patent

The Metaverse Standards Forum (MSF) was announced on June 21, 2022. The MSF aims to “foster interoperability standards for an open metaverse”, and its existence could accelerate the development of metaverse technologies. This article will provide an overview of Standards Development Organizations (SDOs) and how they advance technologies through cooperation among competitors. It will also explore how and why MSF seeks to differentiate itself from SDOs, particularly in terms of intellectual property.

(For those interested in what the Metaverse is, please see our previous Holland & Knight articles: The Metaverse: Building a Fairer World in Virtual Reality and The Metaverse: Patent Infringement in Virtual Worlds.)

I. What are SDOs?

SDOs are collaborations between competing entities to develop global technology standards. In the absence of these collaborations, competing technologies will appear, incompatible with each other. For example, anyone who has traveled beyond North America quickly learns that other countries do not use the same power outlets as we do. To solve the problem, travelers must carry bulky converter boxes to connect their electronic devices to outlets in foreign countries.

This problem could have been solved earlier with a global standard that required all electrical plugs and sockets around the world to meet the same specifications. Although not used worldwide, there is one such standard in the United States for our plugs and receptacles: National Electrical Manufacturer’s Association Specification 5-15.

The socket example illustrates where SDOs focus most of their attention: the interfaces or that space between two components (for example, the plug and the socket). Interfaces are an important part of any engineering project where components need to interact with each other in some way, and engineers will spend a lot of time developing these connections between components. In the power outlet example, manufacturers must install outlets and electronics manufacturers must put outlets on their devices. The interface problem here asks what shape the two ends must have for them to fit together, and what voltage the jack must supply and the jack must receive. By defining the answer to these questions in written standards specifications, plug and socket manufacturers have a point of reference to understand what they can expect from each other.

Because global standardization has never occurred with plugs and sockets, travelers must pack their own separate interface: an AC adapter that can take any type of plug on one end and adapt to any type of socket on the other. These power adapters are actually trophies of inelegant and useless engineering (and I have to admit, I cringe a little every time I put one in a suitcase).

II. The success of SDOs

Although electrical plugs and sockets are not subject to any global standard, many other industries have adopted global standards and found tremendous success in the market. Perhaps the best example of such success is the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), which is developing specifications for global cellular communications.

3GPP was born to solve the “electrical outlet problem” in telecommunications. In the 1980s and 1990s, different geographic regions had different cellular standards. Here is just a partial list of these “1st generation” (1G) standards: AMPS (US and Americas); NMT (Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland and Iceland); TACS (UK); C-Netz (West Germany, Portugal and South Africa); Radiocom 2000 (France); RTMI (Italy); and MCS-L1/L2 (Japan). This splitting of cellular standards meant that your (then very large) phone only worked within national borders. The incompatibility was due to different interfaces between phones and networks from country to country. Indeed, a French telephone and a Norwegian network did not “speak the same language”.

In the early 1990s, the European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) sought to develop a global cellular standard such that the interface between the telephone and the network was fixed and defined. The result was the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM), which was widely deployed across Europe and ushered in many important advances in cellular technologies (including SIM cards and SMS messaging). GSM eventually captured about half of the US market, but even that market was fractured. About half of US cell phones used the IS-95 (CDMA) standard.

3GPP was formed in 1998 to create a truly global cellular standard. It acts as an umbrella organization for SDO partners who had previously developed national cellular standards. 3GPP first grappled with adding data traffic to GSM, then built the first truly global cellular standard, UMTS, which was sold commercially to the public as “3G”.

Since then, 3GPP has developed other global cellular standards familiar to consumers: LTE and 5G. International travelers still need to worry about roaming charges abroad, but their phones will work anywhere on Earth because the communication interface between the phone and any network is now the same worldwide. The story of cellular norms is the story of the Tower of Babel in reverse: fractured languages abandoned in favor of a global language.

The success of 3GPP is obvious to anyone using a smartphone today: 3GPP networks incorporate the best telecommunications ideas available to deliver high-speed data to users. Interestingly, these ideas come from fierce competitors in the cellular market. These competitors collaborate to develop the best possible cellular standards, but each continues to compete to build the best smartphones and infrastructure equipment.

III. Intellectual property rights at SDOs

This mix of collaboration on interfaces and fierce competition on all other elements of a product creates tension over intellectual property rights (commonly referred to as “IPRs”). Entities that participate in SDOs often develop related patented technology at the same time as they define the standards. These entities may wish to have their patented technologies part of the global standard under development at SDO, as global adoption will make these patents more valuable.

To resolve this tension of intellectual property rights between collaboration and competition, SDOs typically require participating entities to openly state that their intellectual property rights are essential to developing standards. (For example, 3GPP requires all of its meetings to begin with a “formal IPR call.”) Entities must declare their IPR so that it is disclosed to all SDO members. If the SDO adopts the patented technology, the reporting company may still benefit from global adoption, but often must agree to license the technology to others on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms.

IV. Enter the Metaverse Standards Forum

Like 3GPP, MSF has positioned itself as an umbrella organization for various metaverse SDOs:

Unlike 3GPP, however, the MSF is explicit that it is “NOT another SDO[,]” and that all standardization activities will take place within member ESOs. MSF will instead focus on promoting

interoperability between these different SDOs.

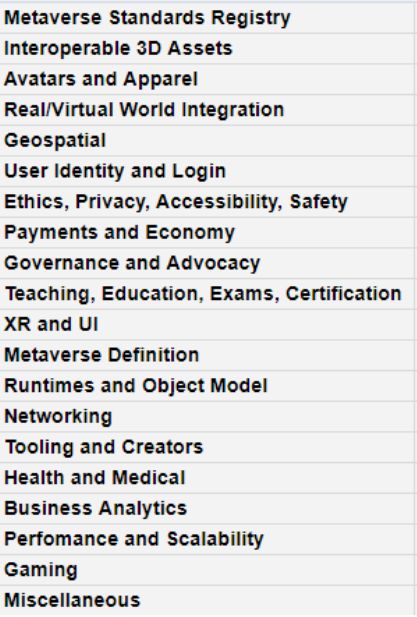

By analogy, the MSF compares the problem it seeks to solve to the problem of interoperable standards in computers. Computers are a collection of various global standards, including Wi-Fi for wireless networking, Bluetooth for short-range wireless connections, HDMI for video output, and USB for peripherals. These different standards must “talk” to each other using standardized interfaces for the computer to work. A similar problem arises in the context of the metaverse. There are a host of SDOs that develop hardware standards (eg, for headsets) and software standards (eg, for virtual assets and virtual worlds). For a system (or systems) to use these metaverse standards, they will need to interact over standardized interfaces. MSF plans to foster interoperability through “prototypes, hackathons, plugfests and tooling projects”. The first list of topics that MSF can work on includes the following, which covers almost the entire realm of the metaverse:

The MSF also distinguishes itself by requiring “no IP framework”. This presumably means that MSF will not have an IPR reporting policy and will not require a license on FRAND terms. Instead, the IPR reporting policies of member SDOs (if any) will prevail.

MSF is just beginning to do its work, but it has the potential to do for the metaverse what 3GPP did for cellular networks: promote the best ideas in the industry, create solutions that benefit consumers, and accelerate adoption. of technology.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide on the subject. Specialist advice should be sought regarding your particular situation.