Saudi Arabia participates in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals Forum

JEDDAH: For centuries, millions of Muslim pilgrims have taken long journeys to the city of Mecca to perform Hajj, one of the five pillars of Islam. Well-established roads crossed the vast Arabian Desert and followed the traditional paths of the Far East to the north and west of the peninsula, surviving the test of time.

The ancient Hajj land routes from neighboring regions materialized over time as a result of favored trade routes and cultural and trade exchanges. These centuries-old and deeply rooted cultural and religious traditions constitute one of the most important material vestiges of Islamic civilization.

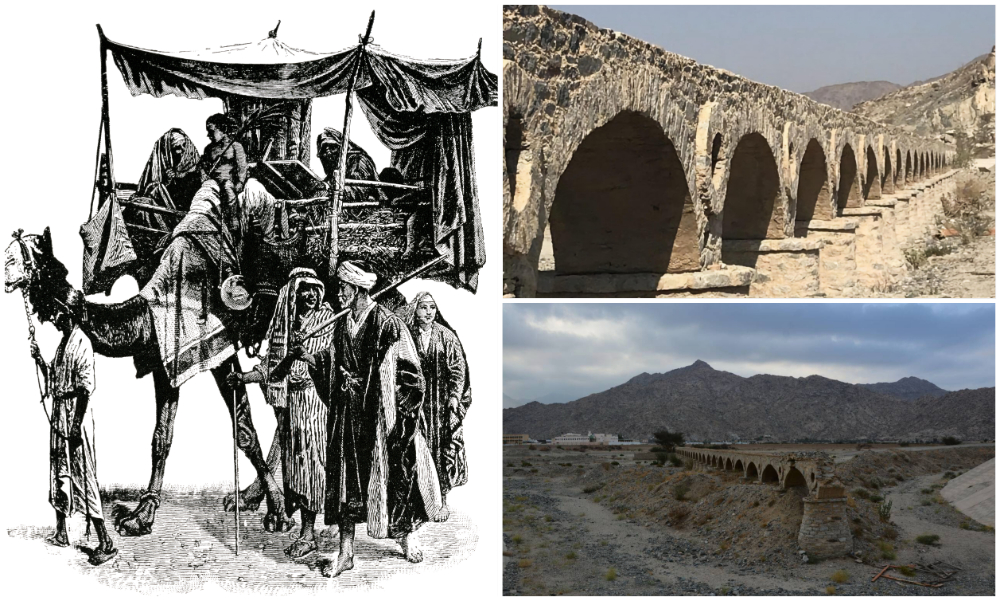

Pilgrims traveled for months in caravans and convoys of camels, horses and donkeys, stopping at wells, pools, dams and stations set up by passers-by, following some of the most famous routes in the Hajj in the footsteps of millions of pilgrims before them on the spiritual journey of a lifetime.

“And proclaim to the people that the Hajj; they will come to you on foot and on every skinny camel; they will come from all the distant passes. Quran 22:27.

Scholars believe that five main routes reached Mecca; others say there could be as many as six or seven, but they are considered secondary roads. The four main ones are the northeastern Kufi route, known as Darb Zubaidah, the Ottoman or Shami (Levantine) route, the northwest African or Egyptian route, and the southern and southeastern Yemeni land and sea routes. and Omanis, also known as the Indian Ocean route.

Stretching over 1,400 km through present-day Iraq and Saudi Arabia, the Kufi route was used as a route to Mecca even in pre-Islamic times. Also known as the Zubaidah Trail, it connects the Iraqi city of Kufa with Mecca, through Najaf and Al-Thalabiyya to the village of Fayd in central Arabia.

The trail then turns west to Medina and southwest to Makkah, passing through the vast and treacherous desert sands of the Empty Quarter, Madain Ban Sulaym and Dhat Irk before reaching Makkah.

Historians believe the Zubaidah Trail was named after Zubaidah bin Jafar, wife of Abbasid Caliph Harun Al-Rashid, both for her charitable work and the number of stations she ordered to be established along the trail. . The ancient path was also a known trade route, gaining prominence and flourishing during the time of the Abbasid Caliphate between 750 and 1258 AD.

The trail is a UNESCO World Heritage candidate site, similar to the Egyptian route, which has also caught the attention of Muslim rulers throughout history. These rulers established structures on the way such as pools, canals and wells.

Some of the routes to Makkah date back to the pre-Islamic era, while the well of Zubaidah (right) has refreshed pilgrims and locals in Makkah for more than 1,255 years. (Universal History Archive/AFP)

They also built barricades, bridges, castles, forts and mosques. Researchers have discovered numerous Islamic inscriptions and memorial writings carved on rocks by pilgrims as they traveled the route to remember their Hajj journey.

Over time, these structures have mostly deteriorated or been destroyed by raids, but many of them have left remnants that shed light on the history and heritage of Arabia.

From the west, the Egyptian Hajj Trail benefited the masses of Muslim pilgrims from Egypt, Sudan, Central Africa, Morocco, Andalusia and Sicily who transited through Cairo. The trail crosses the Sinai to Aqaba, where a fork splits the road in two. The first split is a desert trail that heads towards the holy city of Medina and across vast valleys towards Mecca. The other is a coastal path that follows the Red Sea through Dhuba, Wajh and Yanbu, then heads east to Khulais and southeast, reaching Makkah.

The course of this trail changed over time, depending on political circumstances and technological development, and at some point it intersected with the Ottoman or Shami trail.

Perhaps one of the best-documented Hajj journeys is found in the manuscripts of Moroccan scholar and explorer Ibn Battuta, which describe the journey through numerous illustrations and notes.

Propelled by the quest for adventure and knowledge, Ibn Battuta left his hometown of Tangier in 1325. He took the African route, traveling overland along the Mediterranean coastline to Egypt and seizing the opportunity to learn about religion and law and meet other Muslims. scholars.

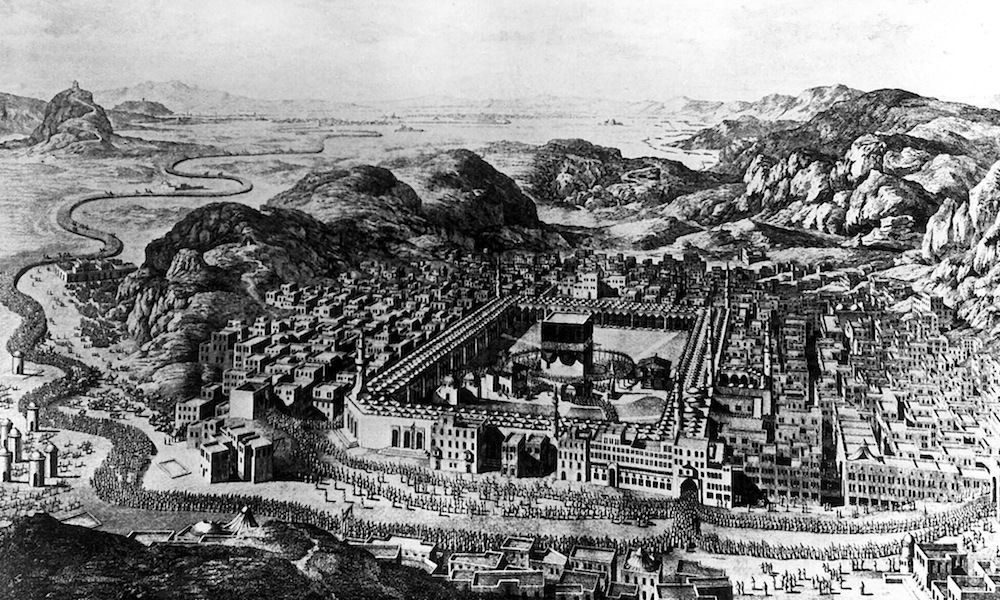

The Islamic Holy Shrine in the courtyard of Masjid Al-Haram (Holy Mosque) in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. Engraving by Mouradgea d’Ohsson, Paris, France, 1790. (Photo: ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images)

More than a year into his journey, Ibn Battuta took a less traveled route through Egypt’s Nile Delta to the Red Sea port of Aydhad, and from there by ship to Jeddah from the other side of the Red Sea coast. His travels took him to Jerusalem, then to Damascus, before finally joining a caravan of pilgrims following the trail of the Levant in 1326.

Connecting the Levant with Makkah and Madinah, the trail begins in Damascus, passes through Daraa, then crosses Dhat Hajj north to Tabuk, Al-Hijr and Madain Saleh, then continues to Madinah. Pilgrims from the north often stayed in the holy city, visiting the Prophet’s Mosque before continuing their journey to Mecca. Many pilgrims returning by road settled in Medina for generations to come and would welcome passing caravans from their homelands.

Since ancient times, Yemeni roads have linked the cities of Aden, Taiz, Sanaa and Saada to the Hijaz region in western Saudi Arabia – one path adjacent to the coast and another crossing the southern highlands of the Asir mountains. Although it could be considered a main route along the Yemeni route, the Oman trail, considered secondary, saw pilgrims travel from Oman along the coast of the Arabian Sea to the Yemen.

Over time, facilities to facilitate the movement of pilgrims provided water and protection along these routes to Mecca and Medina.

Funded by rulers and wealthy patrons, the roads of Egypt, Yemen, Syria and East Asia remained for centuries. No traveler traveled empty-handed, as some carried goods to pay for their journey, and others carried local news that they shared between provinces.

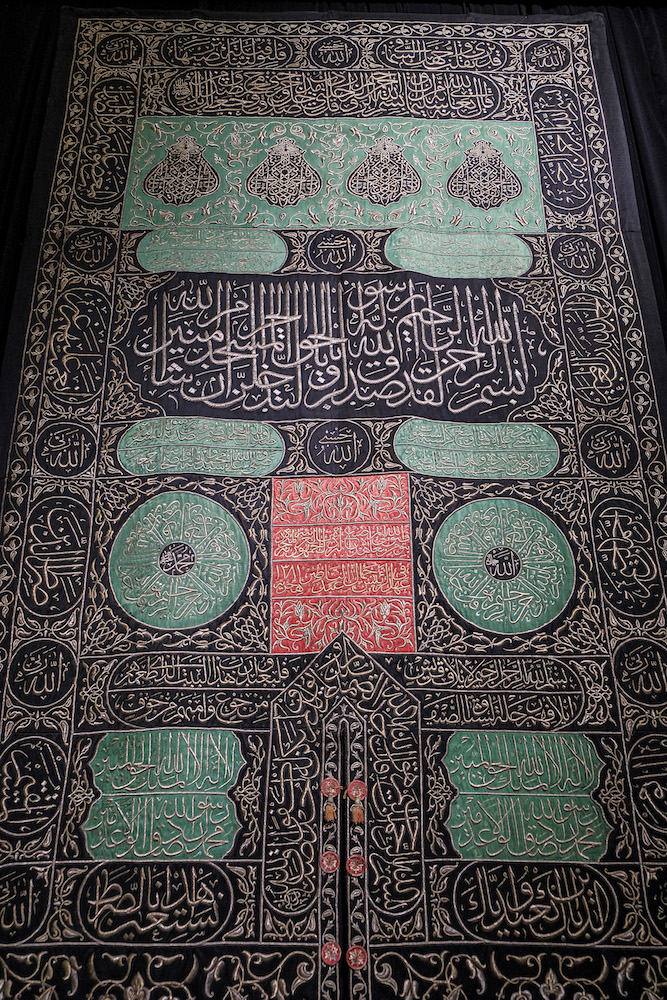

This file photo taken on May 26, 2021 shows a fragment of the Kiswa, the cloth used to cover the Kaaba at the Grand Mosque in the Muslim holy city of Mecca, the last provided by Egypt (in 1961) during the administration of President Gamal Abdel Nasser, on display at the new National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC). (AFP)

For generations scholars have made their journeys to the city, contributing their concepts and ideas, contributing to the scientific enterprise and documenting the journey, noting the historical and cultural significance of the pilgrimage. Many of these scholars remained in Makkah. Others settled in Medina or headed north to such important Islamic cities as Kufa, Jerusalem, Damascus and Cairo to continue their education.

Prior to the 19th century and the modern age of travel, these journeys would have been long and perilous. Although the actual ritual has remained unchanged for over 1,300 years, the difficulties and means of reaching the city of Makkah have lessened and changed beyond recognition, with jets carrying people, buses and cars replacing camels, and Hajj reservations made with the help of the internet.

The roads died out barely half a century ago, but they are well documented and kept in memory as they symbolize the hardships pilgrims went through to perform Hajj. They will forever preserve the spiritual traces of millions of devout Muslims on their culminating journeys.

Pilgrims from all over the world shared a spiritual longing that took masses of pilgrims across oceans, deserts and continents, just as it remains to this day and grows from year to year.