Open Forum: Puerto Rico Shares Some of St. Croix’s Rich Maroon History

Since the transatlantic slave trade, enslaved Africans have exploited geographic migration patterns for freedom. As a result, escaped slaves became a “thorn in the flesh” for the colonial plantation system in the West Indies. These enslaved Africans not only fled from plantation to plantation, but also to the mountains, forests, swamps, towns, villages, ships and adjacent islands of the Caribbean archipelago. It is for this reason that the term “Maritime Maroon” has become known, especially among smaller Caribbean islands such as the Danish West Indies.

In 1760, the landmass of St. Croix was almost entirely cultivated with sugar cane. At the beginning of the 19e century, there were about 181 large plantations with 27,000 enslaved Africans, about half of whom were born in Africa. During this period, 32 million pounds of raw sugar (muscovado) were produced, making St. Croix the fourth largest sugar producer in the world. For the merchants and planters of the Sainte-Croix sugar economy, it was the “golden age” when sugar was king. Believe me, it was not so with the enslaved populations; it was hell.

Nevertheless, throughout the island of Sainte-Croix, refuges for escaped slaves have almost completely disappeared. Goat Hills and Seven Hills in the East End neighborhood of St. Croix were a temporary haven for runaway slaves. Such a refuge came about due to the decline of agricultural activity after 1820. The eastern end of Sainte-Croix became depopulated and the wilderness gradually began to take over. The rugged, wooded terrain of Mount Eagle and Blue Mountain provided shelter for escaped slaves from surrounding plantations.

The dry scrub vegetation forest of Sandy Point on a salty peninsula was another refuge that arose for escaped slaves in the 1820s and 1830s. However, this camp did not last long – only about 10 years due of the overwhelming force of the Danish government. Thus, Northwest St. Croix continued to be a Maroon sanctuary until our emancipation in 1848. There are no other places in the Virgin Islands named Maroon Ridge. If you have common sense, which we’re all meant to have, then you should know that Maroon Country should hold a special place in our hearts for those who made the ultimate sacrifice for our freedom.

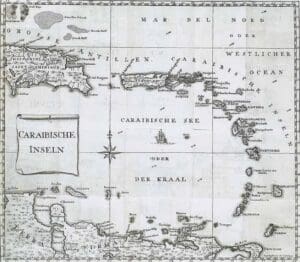

This sixth article in a series concerning the protection and preservation of the establishment of a maroon territorial park on the northwest quarter of St. Croix, focuses on the fact that Puerto Rico has become the main refuge for maroons. Maritimes of the Danish West Indies, although the slaves fled to other places in the Caribbean. On a clear day from northwest of St. Croix, you can see El Yunque Mountain in Puerto Rico and the hills of Vieques (Crab Island) on the horizon of the Caribbean Sea.

These peaks brought hope of freedom to runaway slaves in the Danish West Indies. In 1779, Fernando Miyares Gonzales, a Cuban-born military officer in Puerto Rico, observed sea maroons from the Leeward Islands, including Danish slaves seeking freedom around San Juan. Then there was a Spanish clergyman and historian named Frav Agustin Abbad V Lasierra, who also mentioned that he observed sea maroons or refugees at San Mateo de Cangrejos on the north coast of Puerto Rico.

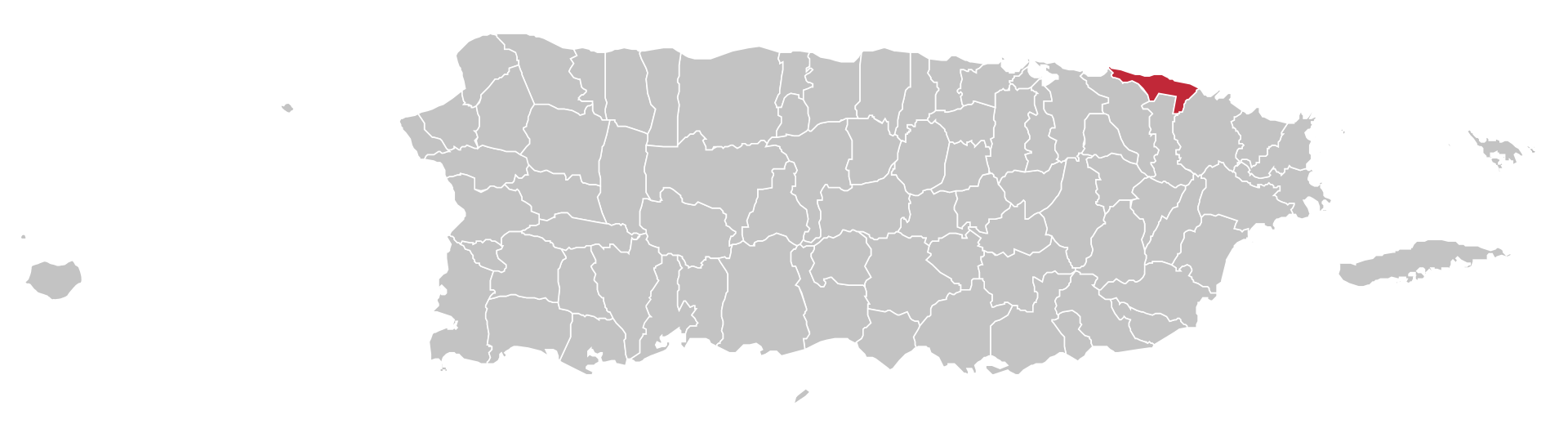

Undoubtedly, some of these Maroons from the Maritimes were runaway Danish slaves as many of them settled in the vicinity of San Juan, the island’s capital. Thus, places inhabited by escaped Danish slaves in Puerto Rico included San Mateo de Cangrejos, Pinones, and Loiza between 1656 and the 1800s.

In fact, in 1664, it was four crucian maroons who fled to Puerto Rico and prompted the Spanish government to officially adopt a policy of offering freedom to future runaway slaves who arrived on this island, which led to the creation of a community of runaway slaves. which eventually became known as Santurce. To this day, the area is inhabited by descendants of escaped enslaved Africans from St. Croix Island as well as all of the Virgin Islands who escaped their captors and came to live in Puerto Rico.

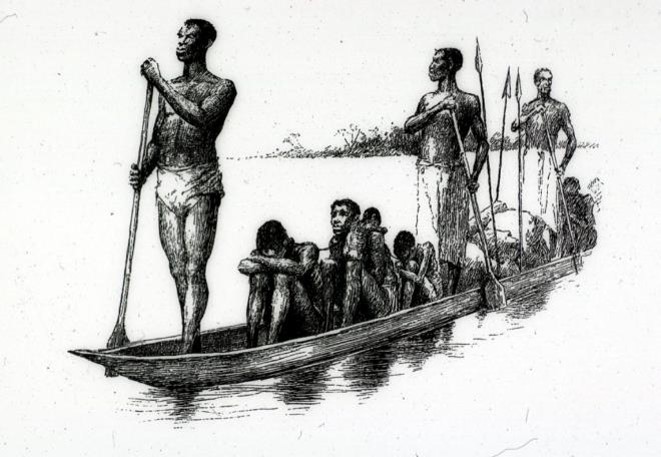

Here are some historical documents relating to the fugitive slaves of Sainte-Croix. This research was compiled by my good friend and colleague, historian George F. Tyson, and Poul E. Olsen on Maroons escaping from St. Croix to Puerto Rico. From the records of the St. Croix Burgher Council from 1767 to 1780: There were several Maritime maroons from the plantations on the north side of St. Croix who escaped to Puerto Rico in a canoe. Mr. Thomas Smith Sr., according to historical records, sailed to San Juan to retrieve the slaves, but was turned away by Spanish authorities. Maroon fugitives were never returned to Sainte-Croix.

Christiansted notarial protocol reported November 6, 1810, stated that three maroons, Jean Baptiste, Heinrich and Jean, were caught stealing a canoe to escape to Puerto Rico, according to Captain Vessup’s report. The three Maroons were condemned to receive 100 lashes and Jean Baptiste, the leader, was expelled from the island.

Proceedings of the St. Croix Burgher Council mention on June 1, 1814 that two enslaved women and 11 enslaved men belonging to Mount Pleasant, St. Georges, Carlton, Plessens, Brook Hill and the Little La Grange Plantation allegedly fled to Puerto Rico for freedom . On February 16, 1827, Andreas Andreson, Master of Police, reported to Governor Peter von Scholten of the Danish West Indies that three enslaved men and a fishing boat from Frederiksted had become maroons. He believed these fugitives stole the boat and fled to Puerto Rico or Vieques.

William Gilbert, a Danish slave, was an unusual case. He escaped to Boston, Massachusetts from St. Croix where he was granted his freedom. In 1847 he wrote a letter to the Danish monarch, King Christian VIII, asking the king to free his family from slavery. Here is part of his letter: “I wrote to my freedom, I have my freedom now but that’s not all sir, I want to see my sisters and brothers and me now as your excellence if your excellence grants me a free pass to come and go when I would be unwilling to come and go to IIe de Sainte-Croix or Santacruce in the West Indies.There is no evidence in Danish records whether Gilbert’s letter received a answer.

When you think of the Northwest, the lost stronghold of the Maroons, you think of freedom.

– Olasee Davis is a bush teacher who lectures and writes about the culture, history, ecology and environment of the Virgin Islands when not leading hikes in the wild places and spaces of St. Croix and beyond.

Editor’s note: Previous columns in this series include “Join the Call for a Maroon Territorial Park,” June 17; “St. Croix’s Northwest Neighborhood Worthy of World Heritage Status,” July 6; “Our Maroon Ancestors Deserve Sanctuary at St. Croix,” July 18; “St. The maroons of Croix prepare the ground for freedom in the Danish West Indies” on July 27; and “A maroon territorial park is not an option but a must,” Aug. 2.