With US inflation settling at a 40-year high of 7.9%, the Federal Reserve finally began to tighten monetary policy, with an initial small increase in interest rates and the promise of more to to come. Getting inflation under control won’t be easy—and the Fed shouldn’t be asked to do it alone.

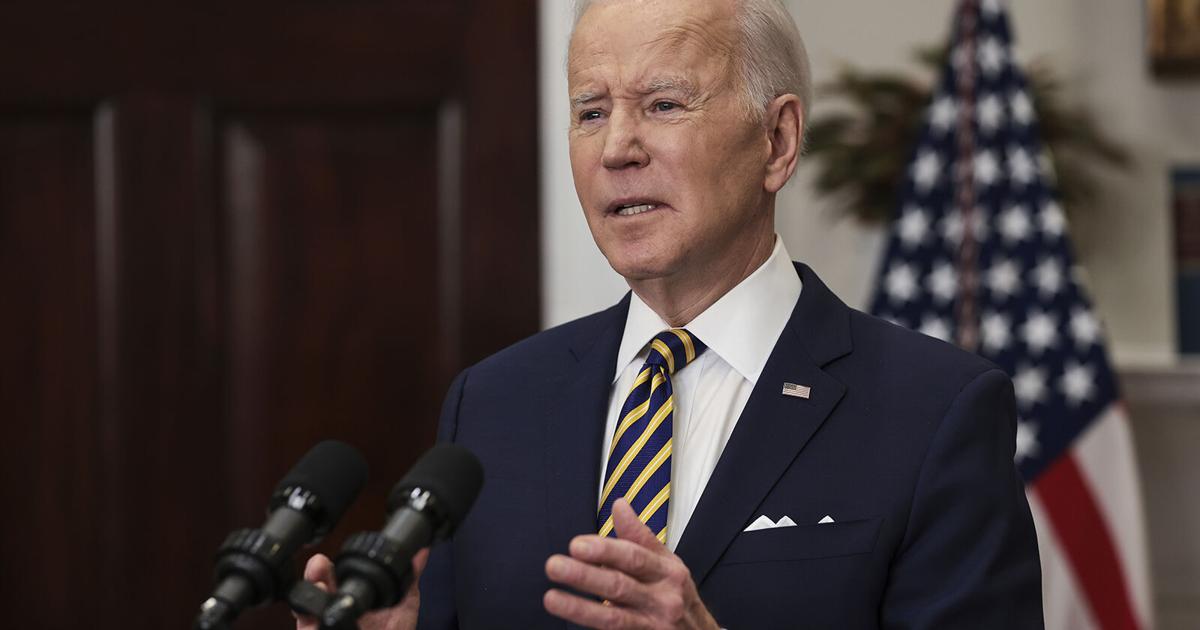

Soaring energy prices compound the problem. President Joe Biden’s recent announcement of a ban on Russian oil, gas and coal imports helped push the benchmark oil price well over $100 a barrel at one point – and the effects of this most recent peak are not yet reflected in the inflation rate. As the war in Ukraine drags on, there could be worse to come. What can be done to alleviate short-term inflationary pressure from rising energy costs?

To tell the truth, less than one would wish. Even so, the Biden administration is not powerless.

Governments should not pretend that consumers can be immune to the economic consequences of Vladimir Putin’s war. Some of the measures being considered, such as the gas tax exemption, would be cosmetic at best. Accusing US oil producers of ripping off their customers is downright counterproductive; the administration needs these companies as partners and not as enemies. On the other hand, ill-designed subsidies for energy production could yield little short-term benefit and could undermine longer-term efforts to combat climate change.

Energy markets are looking to the future. Futures prices rose much less than spot prices after the announcement of energy sanctions against Russia. What producers expect to be paid in the future, and not today, guides their production planning. Short-term supply is relatively tight and new investments are needed to bring new and existing wells online. The challenge is to moderate the upward pressure on prices in the short term, and therefore on inflation, without making fossil fuels more attractive in the long term. Ideally, planned supplies would be delivered earlier, not persistently increased.

The Strategic Petroleum Reserve is one way to achieve this. On March 1, the United States announced that it would release 30 million barrels of crude oil from its stockpile of 580 million. (Other governments have announced their own releases, bringing the total to 60 million barrels.) The release of stocks in the economy eases short-term disruptions. This can and should be combined with advance commitments of later resupply, which would remove supplies from the market and reassure producers that until supplies are replenished and preferably expanded, demand will be sufficient to warrant a temporary increase in production.

The use of so-called swap agreements with the RPD is well established. After Hurricane Katrina in 2005, for example, the SPR loaned refiners about 10 million barrels of oil, and another 11 million were sold on the market. The borrowed oil was repaid in 2007. Such arrangements help stabilize both prices and production. Tensions caused by sanctions against Russia are likely to be more long-lasting and more difficult to manage, but more ambitious use of the SPR could make a difference.

The administration should also explore other ways to boost supply in the short term. Officials are in talks with Venezuela. Negotiations with Iran over the terms of a revived nuclear deal could bring new supplies back to market. Improved relations between the United States and Saudi Arabia offer another opportunity to do the same. All of these initiatives have drawbacks, and a balance will have to be struck between the pressing need to stabilize the global energy market and the risk of jeopardizing other vital objectives.

Note, however, that none of these initiatives should distract the United States and its allies from its efforts to combat climate change. The goal, after all, is not to make fossil fuels cheaper than they would have been without the assault on Ukraine; it is simply a question of limiting the rise in costs in the short term. Efforts to stabilize the market with additional supplies in the near term are consistent with rising fossil fuel costs in the medium to long term, which will accelerate the shift to energy efficiency and low- or zero-carbon alternatives.

The SPR and its counterparts in other countries are finite and, relative to the market as a whole, small. Who knows if the disturbances due to Russian aggression will get worse, or how long they will persist. Reserves cannot solve the problem. But they can help in the moment – and that’s exactly the kind of emergency they were designed for.

The editors are members of the Bloomberg Opinion Editorial Board.