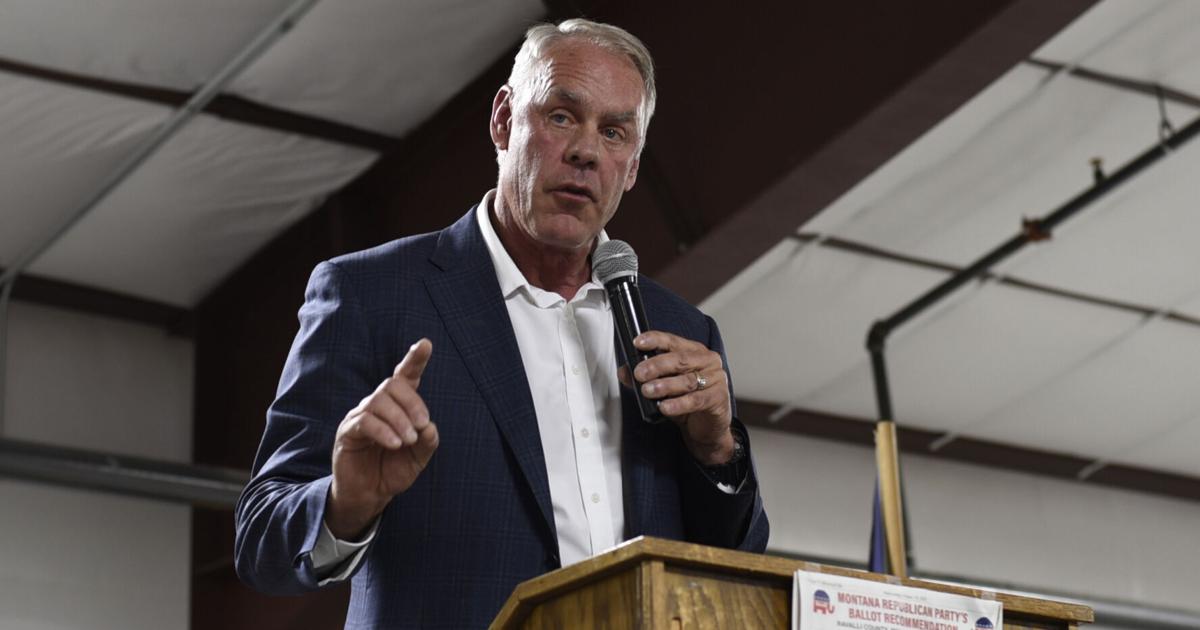

An economic summit with a purpose – by Roy Green

A jobs and skills summit will open in Sydney tomorrow amid inflation, rising interest rates and skills shortages that further weaken Australia’s industrial infrastructure. Here, Roy Green examines the summit landscape and what it means for industry policy.

Although this week’s Jobs and Skills Summit takes place under different circumstances than its 1983 Hawke-Keating predecessor, the point of both is the same. That is to say to generate a consensus not only around the distribution of wealth but also its production.

The popular truism that you have to make the pie bigger to divide it remains a truism of obvious validity. But the relationship between production and distribution in a modern economy is more complex than the truism allows.

Henry Ford’s genius was to raise wages to a level that would reduce absenteeism from work, increase productivity, and enable labor to purchase the products it was proud to produce. This is the beginning of the industrial middle class.

In his practical, business-oriented way, Ford anticipated the ideas of John Maynard Keynes who established the role of effective demand in stimulating non-inflationary growth throughout the economy, with government pulling the levers budgets.

The problem in Australia is that we have reached the limits of demand management as an engine of growth, after the massive stimulus measures applied during the Covid-19 crisis. We now have full employment alongside skill shortages in key sectors of the economy.

We are also experiencing an inflationary surge, but unlike the 1970s and 1980s, this apparent recovery has its origins not in domestic wage pressures but in supply-side factors, such as global supply chain disruption. , weather events and monopoly growth.

Treasury analysis found Australian business ‘margins’, measuring the gap between production costs and prices, increased by 6% over a 15-year period. This is associated with a slowdown in the “dynamism” of firms, as fewer high-productivity firms start up and fewer low-productivity firms exit.

Previous research by the US Federal Reserve has shown that when an industry is concentrated, the costs it passes on to consumers “increase by about 25 percentage points”. Instead of productivity-enhancing competition, the result is innovation that stifles focus.

This is a global phenomenon, reflected in the European Central Bank’s conclusion that “profits have recently been a key driver of total domestic inflation”. And yet, assuming that if you have a hammer, everything looks like a nail, our own Reserve Bank is focusing on demand with interest rate hikes.

The inevitable result will be slower growth and reduced ability to service our debt, except to the extent that the current commodity price spike offers temporary fiscal relief. This brings us to the supply-side challenge that must be addressed in any credible plan for long-term growth and jobs.

We are already seeing that Australia’s narrow trade and industrial structure, based on the export of unprocessed raw materials, makes us more vulnerable to external shocks. It also hampers our ability to transition to a more competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy.

The latest Harvard Economic Complexity Rankings, which measure the diversity and research intensity of exports, show Australia slipping further to 91st out of 133 countries, just ahead of Namibia. Meanwhile, our manufacturing trade deficit has doubled over the past two decades to $180 billion.

Instead of addressing this challenge, the previous government allowed R&D spending to drop from 2.2% of GDP to 1.79%. The OECD average is 2.4%, with countries like Israel, Korea and Switzerland increasing their commitment beyond 4 or even 5%.

Most advanced economies today pursue ambitious industrial policies, not only to correct “market failures”, but to shape markets around clearly defined national missions. For example, the Biden administration’s $280 billion Chips and Science Act is a set of overtly interventionist measures aimed at transforming existing industries and creating new ones.

By globalizing the Australian economy, the Hawke-Keating government prepared industry for change with structural adjustment policies. However, the subsequent growth of “elaborate manufactures” in global markets and value chains was interrupted by the commodity boom.

The windfall gains from rising commodity prices have certainly boosted our national income, but they have also pushed the dollar higher, rendering much of our manufacturing uncompetitive. And they masked the deterioration in our productivity performance, now linked to wage stagnation.

Although it has fallen to 6% of GDP, making Australia the least self-sufficient economy in the OECD, manufacturing still accounts for the largest share of business R&D. In addition to being an industrial sector, it is a capability that drives an ecosystem of infrastructure and related services.

While the emerging consensus on skills development is welcome, its success will depend on government and stakeholder engagement in a broader industrial transformation agenda. Clearly, this is not about the industrial protectionism of the past, but about capitalizing on the industries and technologies of the future.

Nor is a framework of industry-level wage agreements incompatible with firm-level productivity bargaining. This has been the practice in Germany and other countries for many decades, and no doubt contributed to their economic success.

The fact is that workers in these countries also have the opportunity to participate in key decisions of their companies, so that they constantly renew their competitive advantage. This ensures that salary negotiation is not primarily about cost reduction, but about a commitment to value-added innovation and structural change.

For Henry Ford to promote demand for his products, his factories first had to manufacture them. What will Australia choose and how will our strategic choices be determined in the context of a disrupted global division of labour, heightened geopolitical risk and ongoing climate change?

These are the “big picture” issues that should be at the center of the Albanian government’s draft white paper on employment, following the summit. They should certainly be at the heart of a country eager to reinvent its future as a place of creation.

We just need the institutional capacity to translate this vision into reality. This is the goal of a well-designed industrial policy.

Roy Green is Professor Emeritus at the University of Technology Sydney and a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of @AuManufacturing.

Photo: Roy Green

Subscribe for free to our @AuManufacturing newsletter here.